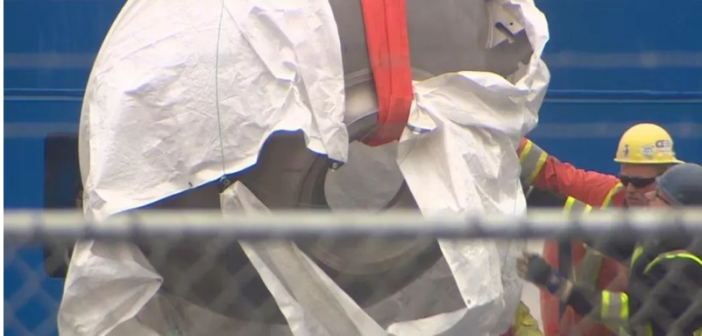

Twisted pieces of the doomed 22-foot submersible Titan were unloaded from the Horizon Arctic ship at a Canadian Coast Guard pier in St. John’s, Newfoundland, on Wednesday. They were covered in white tarps before cranes lifted them onto trucks taking them to an official investigation site. Among the wreckage: the titanium end cap that held the sub’s 21-inch wide porthole; the porthole was missing.

All five people on board the sub died in what the U.S. Coast Guard said was “a catastrophic implosion” just one hour and 47 minutes after the Titan deployed from the Canadian expedition ship Polar Prince on Sunday, June 18. It was headed for the wreck of the Titanic, about 12,500 feet under the surface.

An international search and rescue mission was launched to try to find the sub, eventually covering an area twice the size of Connecticut. The U.S. Navy said that its super-secret sonar devices, intended to track enemy submarines, heard an explosion at the time and location that the Titan went missing. It reported the findings to the Coast Guard, which was in charge of the search-and-rescue effort.

On Thursday, June 22, The Coast Guard said that a remotely-operated-vessel (ROV) had found a wreck field of debris from the Titan about 1,600 feet from the bow of the Titanic.

An implosion of the sub thousands of feet underwater meant that all five on board perished in milliseconds. James Cameron, the director of the Titanic movie who has become a dive expert, said the implosion would be like ten sticks of dynamite going off inside the sub.

Those on the Titan:

Stockton Rush, 61, the CEO of OceanGate, based in Everett, Washington, that built and owned the sub. He was the pilot on this dive, steering the sub with a device that looked like a video-game control.

Hamish Harding, 58, a British explorer and founder of a private equity firm.

Paul-Henry Nargeolet, 77, a French explorer who had made more than 35 dives to the Titanic.

Shahzada Dawood, 48, a British businessman from one of Pakistan’s wealthiest families.

His son, Suleman Dawood, 19, a university student.

After the accident, it turned out that many industry leaders had warned Rush and OceanGate about problems with the Titan’s testing and construction. The U.S. Coast Guard opened an investigation into the loss; so did the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, since it was the authority for the Polar Prince.

At a press conference in Boston, Coast Guard Captain Jason Neubauer said that the investigation would look at the “accountability aspects of the implosion,” and said it may result in “recommendations to the proper authorities to pursue civil or criminal sanctions, if necessary.”

But the investigations are wading into a legal morass. The accident occurred in international waters, about 400 miles south of St. John’s and 900 miles east of Cape Cod. The Titan was registered to OceanGate Expeditions, in the Bahamas. It was launched from a Canadian ship, and the victims were from several different countries.

There was also the legal question whether the Titan fit the definition of a “vessel” under international law, since it could not operate on the surface.

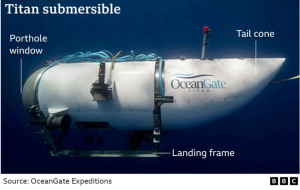

The Titan was 22 feet long, 9’ 2” wide and 8’ 3” high. It basically was a carbon-fiber tube with two titanium end caps, one with the porthole, and landing legs. There were no seats inside. The passengers sat on the floor with their backs against the curved wall. Once inside, they could not get out on their own. The entry hatches were locked from the outside. The sub weighed 23,000 pounds and could travel at 3 knots underwater, powered by four electric thrusters. There was enough air on board to last, theoretically, for 96 hours.

The Titan had made two previous dives to the Titanic since 2021, charging $250,000 per person. But there had been questions about its safety going back many years.

Rush, an aerospace engineer with a family fortune, co-founded OceanGate in 2009. He originally wanted to be an astronaut, but his eyes weren’t good enough. He also was entranced by the underwater world, earning his scuba certification when he was 14. He said he wanted OceanGate to be the SpaceX of the ocean, and it started out with a yellow submarine making shallow dives.

Rush was a man in a hurry, wanting to carve out a niche in adventure travel. But he ran into warnings about his safety procedures years ago. In January, 2018, David Lockridge, OceanGate’s director of marine operations, wrote a report warning of “the potential danger to passengers of the Titan as the submersible reached extreme depths.” He said the viewport was certified to withstand pressure from depths less than half the distance down to the Titanic. (OceanGate ultimately fired him.)

A few weeks later, a group of three dozen industry leaders, including oceanographers and deep-sea explorers, sent Rush a letter warning that OceanGate’s “experimental” approach could lead to “catastrophic” problems.

The New York Times quoted Will Kohnen, the head of the Marine Technology Society, saying, “We suggested, ‘Look, you’re going too fast, and the idea of bypassing the existing classification process can lead to serious consequences. You don’t know what you don’t know.’”

Responding to criticism, Rush wrote an email, as reported by the BBC, that he was “tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation.”

In April, 2019, Carl Stanley, who has run a tourist submersibles business in Honduras for decades, took a dive on the Titan with Rush; they went down 12,000 feet off the Bahamas. The sub made such cracking noises that Stanley urged Rush to cancel a dive to the Titanic that he had advertised for that June.

For its part, OceanGate issued a statement last week, saying “These men were true explorers who shared a distinct spirit of adventure, and a deep passion for exploring and protecting the world’s oceans.”

The Titanic, the largest ship in the world at the time, sank on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York, on April 14, 1912, after it hit an iceberg. Some 1,500 people died in the tragedy.

Read more: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-66045554